How To Revolutionize An Industry, Twice

The Spider-Verse Playbook

(Throughout this article, I’m going to use the abbreviations ITSV and ATSV to refer to ‘Into the Spider-Verse’ and ‘Across the Spider-Verse’. Light spoilers for both films ahead.)

written by: jess kerubino

︎

︎

edited by: stephen shadrach

^dust-covered spider-man relics litter a bedroom I haven’t slept in all year

No other month in the year invites you out to the movies the way early June does. I don’t need further convincing to stay out later into the evening, unwinding under the lights with a £5 student ticket in full-blast air con. A summer ritual I can always count on this time of year.

This term, however, has felt a little different; I’d been in an unproductive slump for months, I hadn’t been to a cinema since April (for normal people imagine if you just disappeared from work for 2 months. this is how it was for me) and my most recent watch was a short film I got into for free as a festival volunteer (i was the world’s worst, most apathetic guest liaison, but it’s fine because they didn’t reimburse me for the train or hotel even though they said they would hahahahaha I’m not still waiting on that cheque!). But none of that mattered last Monday. There wasn’t an option to miss this. South London in June was calling my name and Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse had been released the previous Friday. Standing outside Peckhamplex, I’m grateful that it’s cool in the evening under the shelter, and that my friend agreed to my frenzied 5 am text to join me. We pay for our tickets and head inside.

When the film ended, cheers, shouts, giggles and gasps of awe rippled through the audience. We couldn’t believe what we’d just seen. Coming from someone who has followed production news almost weekly since the last film’s release, the Academy Award-winning Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, I have to say I honestly couldn’t have anticipated everything the sequel delivered. It’s an insanely distinct blend of the crew’s collective skills and styles, a very unique experience to witness on the big screen, and a testament to filmmaking in any form it can squeeze itself into.

Practically bursting with life and colour in every frame, ATSV takes us on a new adventure that sees our heroes, Miles Morales (Shameik Moore), Gwen Stacy (Hailee Steinfeld), and Peter B. Parker (Jake Johnson) reconcile with each other a year and a half after the events of the previous film, with the delightful cinematic debuts of lesser-known-but-beloved fan favourites; Miguel O’Hara (Oscar Issac), an Irish-Mexican Spider-Man doubling as a slick cyberpunk antagonist from the year 2099, an endearing Pavitr Prabhakar (Karan Soni), hailing from Mumbai, Earth-50101, and a mouthy instigator in the form of anarcha-feminist darling Hobart “Hobie” Brown (Daniel Kalyuua), as Spider-Punk (mega win for black British kids with huge geometric-as-fuuuck ‘fros and broken leather boots btw — I love us, we’re so cool), just to name a few of dozens of new characters who’ve recently joined the cast. The all-swinging, all-dancing pack of spiders quip, fight and bound through the vibrant worlds webbed together, as new perils threaten the fate of the multiverse.

The multiverse concept wasn’t at all new when ITSV premiered in 2018, nor had it been a story device exclusive to superhero films (think Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Space Jam, Fantasia if you wanna really go back), but a post-ITSV world saw the concept explode in popularity, with countless franchises all rushing to build (often poorly) extended universes running on the ever-ephemeral currency that is IP.

Yes, there are countless references to sixty years of media based around this one guy (and the many iterations of his character), but it doesn’t scare away its viewers with the daunting experience of catching up with a plot you’ve got no background on. ATSV tells a compelling story about Miles finding his place in the multiverse on his own terms, despite the unrelenting feeling that he isn’t enough, that he’ll never be enough, even after everything he's done to prove himself up to this point (god…don’t I know it). Gwen Stacy and her father Captain Stacy, and Peter B. Parker’s family with M.J. and Mayday also have full, emotional story arcs of their own, and it’s an absolute joy to see our characters grow and change whilst grappling with themes of insecurity, guilt, identity and belonging.

![]()

![]()

^miles beating the shit out of like 30 different peters at one point >>>>> like yeah i raised him like that get him again

It’s no wonder Across The Spider-Verse is such a triumph; it’s made by the most exciting names in animation and slapstick comedy of the 2010s. The three directors, Kemp Powers, Joaquim Dos Santos and Justin K. Thompson had all been involved in related work before joining the crew. Powers, just having directed Disney Pixar’s Soul (2020), was announced in 2021, while the project was in its planning phase. You can see some of these leftover ideas from Soul carry on into ATSV, like the contorted portal-travelling physics with Spot, or the construction of an ever-sprawling animated city that’s just as boisterous and as bouncy as the main cast. Dos Santos, with a background in storyboarding, brought his experience of animating deft action and complicated fight scenes from projects Avatar: The Last Airbender (2010) and Voltron: Legendary Defender (2016 - 2018), and Thompson worked as a production designer on the Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs franchise before taking on the same role for ITSV and the PS5 ‘Spider-Man: Miles Morales’ game (let me tell you — the day this suit announcement dropped me and my friends were HOLLERING all day about a game we couldn’t yet play nor afford).

So, how do you bring together a team that’s so suited to the wildly ambitious goal of a film that features multiple, different, fully formed worlds, with their own distinct colour palettes, visual language and environmental physics? Not to mention an abundance of new faces, backgrounds and timeline details to keep track of. It would help if you’ve done it a couple of times before. Produced and written by returning producers Phil Lord and Chris Miller, ATSV boasts what might be my favourite crew of any film ever, starting with the first names to be attached to the ITSV back in 2014.

A few years ago, instead of focusing on my A-Levels, I went through a period of deeply immersing myself in everything Phil and Chris had worked on before ITSV’s release. I studied their careers extensively, and I’m almost embarrassed to admit how well I can map out their journey; from collaborating at Dartmouth to getting fired by Disney (twice — brb, starting a production company called Fired Solo Directors Entertainment), then a brief stint at MTV in 2002 that resulted in Clone High, a hilariously awkward, nonsensical animated comedy with a particularly solid first season that revealed where the duo’s strengths lie. Heavily stylized sequential art and comedic storytelling was clearly their game, and having established themselves as producers, went on to work at Sony Pictures Animation, directing and producing titles like Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs (2009), The Lego Movie (2014) and its sequel, and The Mitchell’s Vs. The Machines (2021), as well as the revived 21 Jump Street franchise (2012, 2014) for Sony Pictures Entertainment.

Hopefully, you can kind of predict the perfect storm this repertoire was leading to. Both Cloudy and The Lego Movie used a lot of different, newer animation processes that previously weren’t being pushed at Sony — Cloudy presented challenges like animating translucent jelly textures, out-of-control machine explosions and large-scale, hyper-detailed foods in software being utilised by the studio only for the second time. Lord and Miller were also fired and re-hired during the first year of production due to what producer Amy Pascal (of Pascal Pictures) saw as a weak emotional arc for the film’s protagonist, Flint Lockwood (Bill Hader). The pair have remarked on this as a vital learning experience that’s influenced the way they approach writing story ever since.

As for The Lego Movie, a special detail about its production was that it was, save for its live-action sequences, animated entirely in computer software, yet mostly plays by the real-life rules of stop-motion animation. You can’t take a shortcut with these hard little bits of odd-shaped plastic that weren’t ever meant to bend sideways, and so all of the pieces in the film are animated true to how kids have always interacted with the toy, going with the approach of preserving the joy of play and discovery in every frame. This, in turn, inspired one particular contributor to ATSV you may have already heard of.

What Across the Spider-Verse does best is that it takes on all the lessons learnt from years of work on various ambitious projects, and completely blows things out of the water with a super-developed follow up. A wonderful example of this is Spider-Punk’s paint-splashed glitches as he sprints, glides and swings weightlessly through the multiverse with the gang, though not quite like the others. He’s animated using lots of different frame rates from head to toe.

“Ultimately what we found worked was a combination of different frame rates for different parts of his body, which no other character has. They’re either 2s, 3s, 1s, whatever. But his jacket is on 4s, his body’s on 3s, sometimes other parts of his body are on 2s. And then his guitar has the lowest frame rate, it’s a lot more, it’s 6s sometimes. That meant we had to have multiple rigs that all had those different settings on them so that it could be put together. He was probably one of the most complicated characters because he had so many different literal layers to him.”

— Alan Hawkins, head of character animation. Read more on ATSV’s character animation here.

![]()

^animator Li Wen Toh’s diagram of how she sets up 2D elements in Hobie’s shots — read her thread here

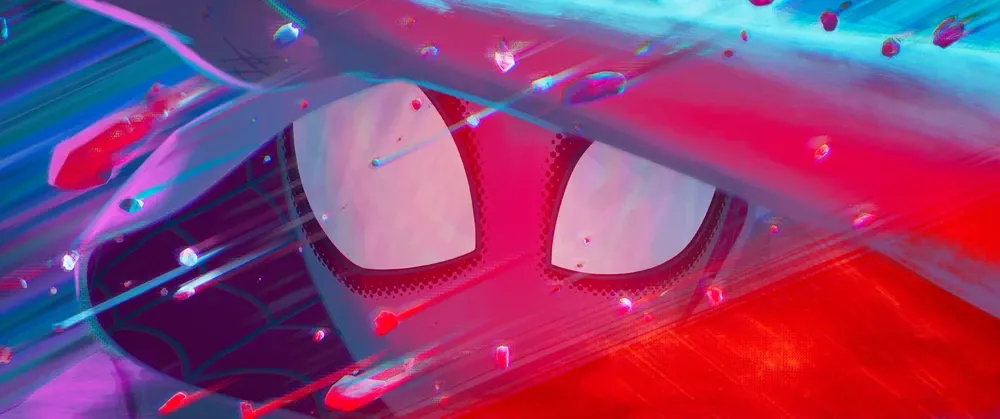

It clearly builds on the work from individual character keyframing in Into the Spider-Verse— remember Miles’ jagged, anxious 12fps movements alongside Parker’s smooth 24fps swinging during the Alchemax chase? Only after Miles gains his strength and confidence as Spider-Man, and it is so unbelievably rewarding to see him animated swinging in all 24 frames of glory.

![]()

During my very short time in sixth form, I would pick through all the artists’ filmographies with a fine-toothed comb, desperately trying to shoehorn whatever I liked about their work into my own. I studied the art-of-the-movie books like they were scripture. I worked through each of them again and again, and I was certain if I could paint with the same vibrance these artists had, sketch out each profile just as they’d done, I’d be able to replicate it all myself one day. I watched the first film almost every week. The soundtrack was stitched into all my conversations, my afternoons spent at the library, my bike rides to school, my unpaid projectionist job…I can’t remember any of these things without ITSV. They aren’t pointless to me anymore. The art of everything Spider-Verse is woven into me for good, and it can’t wrangle itself out, even if it wanted it to!

![]()

colour keys painted by vis dev artist Kat Tsai

“I recommend looking through everything she’s posted from production, her work is immaculate”

ATSV challenges the structure of sequential art-based filmmaking entirely, operating at a whole new level that’s only going to improve from here on out. The film is currently the longest American animated feature to date and boasts the largest crew, over 1000 members, of any animated film in history. It’s been about 2 weeks since the film hit theatres in the UK and it is still beating out any other film showing right now by a mile (😏). Everything is changing; the way we’ll do it now will be so different from before, and this is the point where we’ll look back and know that the flag was planted right here, right now, and it’s red and blue and beautiful, baby!

Across the Spider-Verse encourages the next generation of animators and video makers to get truly weird with it. And this isn’t limited to students in academic institutions by any means (salute you guys though, couldn’t be me) — but young artists from all walks of life; stop-motion fanatics modelling clay in the messiest bedrooms you’ve ever seen, masters of vertical video, 3D Blender whizzes, p5js tinkerers and contemporary filmmakers who want to go above and beyond the limitations of a single camera lens. It begs you to grapple with the experimental, to get messier with the process and to take risks at every step of the way. If there isn’t a point where you wonder if you’ve gone far enough then you haven’t.

There are no bounds to what can be made when you approach the work in this way, and it’s what I love so terribly about animation. I got to hear a friend gushing over the film in a long string of voice notes, wrapping it up by saying ‘I actually don’t have any words — the fact that I don’t have any words and I’m making 6 voice notes…that’s how good the film was’ which is just ridiculously true to the feeling. I could keep typing about Spider-Man, about Miles, the cast, the crew, the power of the panel and collaborative filmmaking and all the rest of it until the keys start falling off. I still wouldn’t be able to put it quite into words the way I feel it deserves.

All I can say is watching ATSV feels like what I’ve been trying to express for years. It asks so much more of what a film, animated or otherwise, can deliver and has introduced many to the joy of non-traditional motion-making, which is, at the core of it all what I’m excited about the most. Let’s go beyond.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is still showing in cinemas.

madeintheurl 2023

Yes, there are countless references to sixty years of media based around this one guy (and the many iterations of his character), but it doesn’t scare away its viewers with the daunting experience of catching up with a plot you’ve got no background on. ATSV tells a compelling story about Miles finding his place in the multiverse on his own terms, despite the unrelenting feeling that he isn’t enough, that he’ll never be enough, even after everything he's done to prove himself up to this point (god…don’t I know it). Gwen Stacy and her father Captain Stacy, and Peter B. Parker’s family with M.J. and Mayday also have full, emotional story arcs of their own, and it’s an absolute joy to see our characters grow and change whilst grappling with themes of insecurity, guilt, identity and belonging.

^miles beating the shit out of like 30 different peters at one point >>>>> like yeah i raised him like that get him again

It’s no wonder Across The Spider-Verse is such a triumph; it’s made by the most exciting names in animation and slapstick comedy of the 2010s. The three directors, Kemp Powers, Joaquim Dos Santos and Justin K. Thompson had all been involved in related work before joining the crew. Powers, just having directed Disney Pixar’s Soul (2020), was announced in 2021, while the project was in its planning phase. You can see some of these leftover ideas from Soul carry on into ATSV, like the contorted portal-travelling physics with Spot, or the construction of an ever-sprawling animated city that’s just as boisterous and as bouncy as the main cast. Dos Santos, with a background in storyboarding, brought his experience of animating deft action and complicated fight scenes from projects Avatar: The Last Airbender (2010) and Voltron: Legendary Defender (2016 - 2018), and Thompson worked as a production designer on the Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs franchise before taking on the same role for ITSV and the PS5 ‘Spider-Man: Miles Morales’ game (let me tell you — the day this suit announcement dropped me and my friends were HOLLERING all day about a game we couldn’t yet play nor afford).

So, how do you bring together a team that’s so suited to the wildly ambitious goal of a film that features multiple, different, fully formed worlds, with their own distinct colour palettes, visual language and environmental physics? Not to mention an abundance of new faces, backgrounds and timeline details to keep track of. It would help if you’ve done it a couple of times before. Produced and written by returning producers Phil Lord and Chris Miller, ATSV boasts what might be my favourite crew of any film ever, starting with the first names to be attached to the ITSV back in 2014.

A few years ago, instead of focusing on my A-Levels, I went through a period of deeply immersing myself in everything Phil and Chris had worked on before ITSV’s release. I studied their careers extensively, and I’m almost embarrassed to admit how well I can map out their journey; from collaborating at Dartmouth to getting fired by Disney (twice — brb, starting a production company called Fired Solo Directors Entertainment), then a brief stint at MTV in 2002 that resulted in Clone High, a hilariously awkward, nonsensical animated comedy with a particularly solid first season that revealed where the duo’s strengths lie. Heavily stylized sequential art and comedic storytelling was clearly their game, and having established themselves as producers, went on to work at Sony Pictures Animation, directing and producing titles like Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs (2009), The Lego Movie (2014) and its sequel, and The Mitchell’s Vs. The Machines (2021), as well as the revived 21 Jump Street franchise (2012, 2014) for Sony Pictures Entertainment.

Hopefully, you can kind of predict the perfect storm this repertoire was leading to. Both Cloudy and The Lego Movie used a lot of different, newer animation processes that previously weren’t being pushed at Sony — Cloudy presented challenges like animating translucent jelly textures, out-of-control machine explosions and large-scale, hyper-detailed foods in software being utilised by the studio only for the second time. Lord and Miller were also fired and re-hired during the first year of production due to what producer Amy Pascal (of Pascal Pictures) saw as a weak emotional arc for the film’s protagonist, Flint Lockwood (Bill Hader). The pair have remarked on this as a vital learning experience that’s influenced the way they approach writing story ever since.

As for The Lego Movie, a special detail about its production was that it was, save for its live-action sequences, animated entirely in computer software, yet mostly plays by the real-life rules of stop-motion animation. You can’t take a shortcut with these hard little bits of odd-shaped plastic that weren’t ever meant to bend sideways, and so all of the pieces in the film are animated true to how kids have always interacted with the toy, going with the approach of preserving the joy of play and discovery in every frame. This, in turn, inspired one particular contributor to ATSV you may have already heard of.

What Across the Spider-Verse does best is that it takes on all the lessons learnt from years of work on various ambitious projects, and completely blows things out of the water with a super-developed follow up. A wonderful example of this is Spider-Punk’s paint-splashed glitches as he sprints, glides and swings weightlessly through the multiverse with the gang, though not quite like the others. He’s animated using lots of different frame rates from head to toe.

“Ultimately what we found worked was a combination of different frame rates for different parts of his body, which no other character has. They’re either 2s, 3s, 1s, whatever. But his jacket is on 4s, his body’s on 3s, sometimes other parts of his body are on 2s. And then his guitar has the lowest frame rate, it’s a lot more, it’s 6s sometimes. That meant we had to have multiple rigs that all had those different settings on them so that it could be put together. He was probably one of the most complicated characters because he had so many different literal layers to him.”

— Alan Hawkins, head of character animation. Read more on ATSV’s character animation here.

^animator Li Wen Toh’s diagram of how she sets up 2D elements in Hobie’s shots — read her thread here

It clearly builds on the work from individual character keyframing in Into the Spider-Verse— remember Miles’ jagged, anxious 12fps movements alongside Parker’s smooth 24fps swinging during the Alchemax chase? Only after Miles gains his strength and confidence as Spider-Man, and it is so unbelievably rewarding to see him animated swinging in all 24 frames of glory.

During my very short time in sixth form, I would pick through all the artists’ filmographies with a fine-toothed comb, desperately trying to shoehorn whatever I liked about their work into my own. I studied the art-of-the-movie books like they were scripture. I worked through each of them again and again, and I was certain if I could paint with the same vibrance these artists had, sketch out each profile just as they’d done, I’d be able to replicate it all myself one day. I watched the first film almost every week. The soundtrack was stitched into all my conversations, my afternoons spent at the library, my bike rides to school, my unpaid projectionist job…I can’t remember any of these things without ITSV. They aren’t pointless to me anymore. The art of everything Spider-Verse is woven into me for good, and it can’t wrangle itself out, even if it wanted it to!

colour keys painted by vis dev artist Kat Tsai

“I recommend looking through everything she’s posted from production, her work is immaculate”

ATSV challenges the structure of sequential art-based filmmaking entirely, operating at a whole new level that’s only going to improve from here on out. The film is currently the longest American animated feature to date and boasts the largest crew, over 1000 members, of any animated film in history. It’s been about 2 weeks since the film hit theatres in the UK and it is still beating out any other film showing right now by a mile (😏). Everything is changing; the way we’ll do it now will be so different from before, and this is the point where we’ll look back and know that the flag was planted right here, right now, and it’s red and blue and beautiful, baby!

Across the Spider-Verse encourages the next generation of animators and video makers to get truly weird with it. And this isn’t limited to students in academic institutions by any means (salute you guys though, couldn’t be me) — but young artists from all walks of life; stop-motion fanatics modelling clay in the messiest bedrooms you’ve ever seen, masters of vertical video, 3D Blender whizzes, p5js tinkerers and contemporary filmmakers who want to go above and beyond the limitations of a single camera lens. It begs you to grapple with the experimental, to get messier with the process and to take risks at every step of the way. If there isn’t a point where you wonder if you’ve gone far enough then you haven’t.

There are no bounds to what can be made when you approach the work in this way, and it’s what I love so terribly about animation. I got to hear a friend gushing over the film in a long string of voice notes, wrapping it up by saying ‘I actually don’t have any words — the fact that I don’t have any words and I’m making 6 voice notes…that’s how good the film was’ which is just ridiculously true to the feeling. I could keep typing about Spider-Man, about Miles, the cast, the crew, the power of the panel and collaborative filmmaking and all the rest of it until the keys start falling off. I still wouldn’t be able to put it quite into words the way I feel it deserves.

All I can say is watching ATSV feels like what I’ve been trying to express for years. It asks so much more of what a film, animated or otherwise, can deliver and has introduced many to the joy of non-traditional motion-making, which is, at the core of it all what I’m excited about the most. Let’s go beyond.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is still showing in cinemas.

madeintheurl 2023